Ce premier état des océans, publié dans le magazine Science, a été réalisé par une équipe de 19 chercheurs dirigée par Benjamin Halpern du National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS) (Université de Californie de Santa Barbara).

Ce premier état des océans, publié dans le magazine Science, a été réalisé par une équipe de 19 chercheurs dirigée par Benjamin Halpern du National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS) (Université de Californie de Santa Barbara).

Why map the human impact to the world's oceans?

What happens in the vast stretches of the world's oceans - both wondrous and worrisome - has too often been out of sight, out of mind.

The sea represents the last major scientific frontier on planet earth - a place where expeditions continue to discover not only new species, but even new phyla. The role of these species in the ecosystem, where they sit in the tree of life, and how they respond to environmental changes really do constitute mysteries of the deep. Despite technological advances that now allow people to access, exploit or affect nearly all parts of the ocean, we still understand very little of the ocean's biodiversity and how it is changing under our influence.

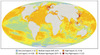

The goal of the research presented here is to estimate and visualize, for the first time, the global impact humans are having on the ocean's ecosystems.

Our analysis, published in Science, February 15, 2008 (no subscription required), shows that over 40% of the world's oceans are heavily affected by human activities and few if any areas remain untouched.

![]() Download the Marine Impacts KML to view the cumulative impact map in Google Earth.

Download the Marine Impacts KML to view the cumulative impact map in Google Earth.

How did we create this map?

There were 4 steps to creating this composite map.

1. We gathered or created maps (with global coverage) of all types of human activities that directly or indirectly have an impact on the ecological communities in the ocean's ecosystems. In total, we used maps for 17 different activities in categories like fishing, climate change, and pollution. We also gathered maps for 14 distinct marine ecosystems and modeled the distribution of 6 others.

2. To estimate the ecological consequences of these activities, we created an approach to quantify the vulnerability of different marine ecosystems (e.g., mangroves, coral reefs, or seamounts) to each of these activities, published in Conservation Biology, October 2007. For example, fertilizer runoff has been shown to have a large effect on coral reefs but a much smaller one on kelp forests.

3. We then created the cumulative impact map by overlaying the 17 threat maps onto the ecosystems, and using the vulnerability scores to translate the threats into a metric of ecological impact.

4. Finally, using global estimates of the condition of marine ecosystems from previous studies, we were able to ground-truth their impact scores.

To learn more about the methods used in this study, see the Supplementary Online Materials in Science.

What does the map tell us?

First, we can compare different locations to determine the least and most impacted regions of the globe.

There are large extents of heavily impacted ocean in the North Sea, the South and East China Seas, and the Bering Sea. Much of the coastal area of Europe, North America, the Caribbean, China and Southeast Asia are also heavily impacted.

The least impacted areas are largely near the poles, but also appear along the north coast of Australia, and small, scattered locations along the coasts of South America, Africa, Indonesia and in the tropical Pacific.

For additional videos of the model and information on the SST data, please visit the National Oceanographic Data Center.

Second, the data summarized in the map provides critical information for evaluating where certain activities can continue with little effect on the oceans, where other activities might need to be stopped or moved to less sensitive areas, and where to focus efforts on protecting the last pristine areas. As management and conservation of the oceans turns toward marine protected areas (MPAs), ecosystem-based management (EBM) and ocean zoning to manage human influence, we hope our study will be useful to managers, conservation groups and policymakers.